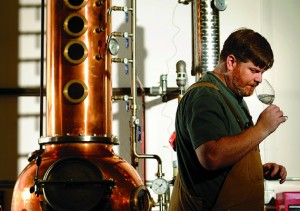

Scott and Todd Leopold began distilling in 2001, and since then demand for their craft spirits and liqueurs has been so high that they’ve already had to expand twice. The tidy, whitewashed new Leopold Brothers distillery in Denver has more than triple the capacity of their last place. They moved their old copper-pot still to the new location, and then added two more identical to it, plus a towering column still. Two of the copper stills will be dedicated solely to producing the brothers’ much-sought-after Maryland-style rye, the latest batch of which sold out in 45 minutes. “Did we foresee this?,” Todd said. “No. I thought I’d be running a small still for the rest of my career. And I was okay with that.”

Scott and Todd Leopold began distilling in 2001, and since then demand for their craft spirits and liqueurs has been so high that they’ve already had to expand twice. The tidy, whitewashed new Leopold Brothers distillery in Denver has more than triple the capacity of their last place. They moved their old copper-pot still to the new location, and then added two more identical to it, plus a towering column still. Two of the copper stills will be dedicated solely to producing the brothers’ much-sought-after Maryland-style rye, the latest batch of which sold out in 45 minutes. “Did we foresee this?,” Todd said. “No. I thought I’d be running a small still for the rest of my career. And I was okay with that.”

Craft distilling-a loosely defined industry consisting chiefly of distillers producing fewer than 50,000 cases a year-is now in its heady, early-Internet phase. There were about 70 small distilleries across the United States in 2003; today there are more than 600. Hardly a day passes without the announcement of a new distillery opening its doors to produce craft gin or bourbon or an obscure liqueur inspired by a Pflümli someone once tasted in Pfungen.

“I’m approaching my sixth year as a consultant in the craft industry,” said Dave Pickerell, a former master distiller at Maker’s Mark. “And 100 percent of the clients I worked with in years one, two, and three have already expanded. And the clients I picked up starting in year four are expanding now.”

Pickerell made his comments in March at the first convention of the American Craft Distillers Association, a brand-new, member-run trade association formed to aid small producers trying to figure out, essentially, how to surf a tsunami. (It’s one of two organizations for small distillers; the older, privately held American Distilling Institute convened its annual meeting a couple of weeks later in Seattle.) Many small distillers I spoke with gave me variations of Pickerell’s story: they’d just launched, but already had to move to new buildings and buy new stills, because they’d underestimated demand.

Given this roaring success, one might have expected the conference mood to be raucous and giddy-especially considering that the people there were basically professional drinkers. Instead, the tone was subdued, and a lot of attendees voiced concern that the craft-distilling industry is growing too quickly.

Some expressed anxiety, sotto voce, that many of the new spirits being released aren’t yet ready for prime time: the liquor is too rough-edged or funky, pitiably less valuable than its $40-a-bottle price tag promises. Given the current fad for local, “authentic” products, selling a consumer that first bottle isn’t too hard. (Folks from Nielsen who attended the conference reported that Gen Xers and Millennials ranked “local” and “authentic” higher as qualities they valued in a spirit than did their Baby Boomer elders, who sought out some obscure factor called “taste.”) But if the quality doesn’t measure up to the price, it’s not hard to imagine a nation of home bars each containing a single, largely untouched bottle of disappointing “craft spirit.”

One reason for the widely varying outcomes from craft distilleries is a shortage of experienced distillers. Maggie Campbell, the head distiller at Privateer Rum, in Massachusetts, told me that she and her assistant distiller (who happens to be her husband) are regularly solicited by new distilleries to come run their operations, sometimes with six-figure salaries as an enticement. “I’ve heard of people with their license, equipment, and still ready to go with no distiller to run the place,” said Campbell, who just turned 30.

I tasted samples of dozens of ryes and bourbons at the conference, and it’s true that many were regrettably coarse and moonshiney. Yet, somehow, these made finding the superior liquors-and there were quite a few-all the more thrilling. For me, those included several of the Leopold Brothers products I tried: the big Maryland rye, the cherry liqueur, and, most impressive of all, the orange liqueur, taking a sip of which was like climbing a ladder through a citrus tree into bright sunshine.

When I visited the Leopolds’ distillery, I stood near their new malt kiln and took in the distant views of the Rockies across the empty two-acre lot just beyond the loading docks. The brothers own that lot, too. They figure that within a few years, they may have to expand again, and so they left room to build a mirror image of their current distillery, to increase capacity once more. Assuming, that is, craft spirits don’t get a bad name in the meantime.

Source: The Atlantic

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/has-craft-distilling-lost-its-spirit/361619/